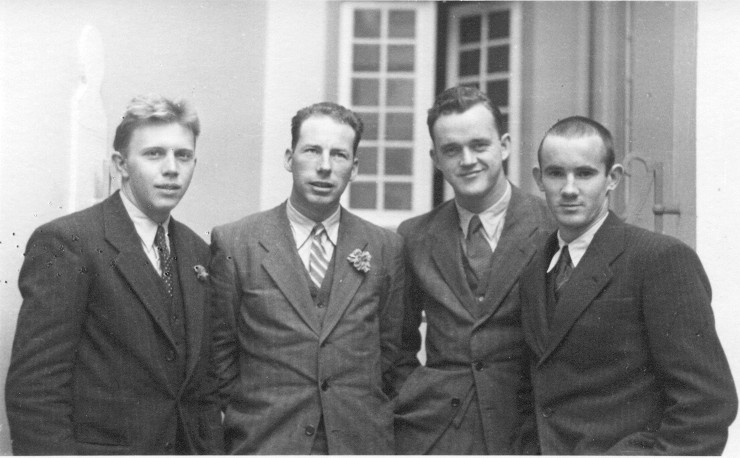

Lyle van Hook, Richard L. Trum, John W. Eden and Julian O. Pierce in Lisbon

(Picture: Lyle Van Hook

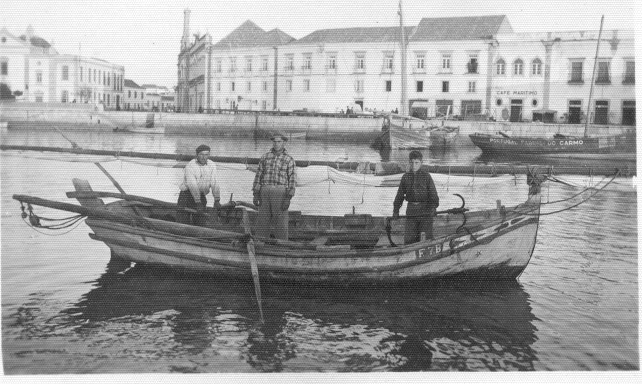

Jaime Nunes, José and Manuel Mascarenhas in the small ship that rescued the airmen

(Picture: Lyle Van Hook

Date

Location

Force

Aircraft

From-To

Crew

30-11-1943

Faro (no mar)

USNAVY VB-112

Consolidated PB4Y-1 (B-24 J) Liberator BuN 63931

Port Lyuatey (Marroco) → Port Lyuatey (Marroco)

Lt Richard Trum USA

Lt John Woodrow Eden USA

Arm3c Earl Edgar Bowers USA †

Arm3c George Austin Doane USA †

Arm3c Donald Eugene Peterson USA †

Arm3c Frank William Taylor USA †

Arm3c William Richardson Stultz USA

Arm3c Rex Lee Mccoy USA

Arm3c Julian O'neil Pearce USA

Ens. Clarence Arthur Miller USA †

Amm2c Lyle Van Hook USA

The pilot became disoriented and reached the Algarve coast - at night - when he should have been in the Port Lyautey area, in Morocco.

Without fuel, he thought he was making a landing on the beach, but he crashed into the sea. Five of the 11 crew perished.

The survivors were picked up by three fishermen who took them ashore.

The story was told to me by two of the participants several decades ago and over the years the story has grown. All the details can be found in the following article:

“That made a splash. It was a monster. Sparks flew everywhere. It smelled of oil and smoke. We were so scared.” It was this way that Jaime Nunes remembered the moment a huge plane crashed in front of him, on the night of November 30, 1943. He was a few miles from Faro, on a fishing boat, when the war, which always seemed so far away, literally fell at his feet.

Since the beginning of the night, he was on the fishing ground where he normally caught croakers. With him were his compadre, José Mascarenhas, and his son, Manuel.

By 10 pm they spotted a strange set of lights in the air. “I saw them go to Quarteira and back. Then they flew over the city of Faro with the lights on. It seemed as they were looking for something”, recalled the fisherman, 50 years after the incident.

The crew of the plane, a PB4Y-1 – the navy’s version of the B-24 Liberator bomber – were indeed looking for a place to land the huge four-engined plane, but were lost after a long patrol in search for German boats and submarines. They belonged to the VB 112 squadron, which had just arrived at Port Lyautey – now Kenitra – in Morocco.

In these patrols the planes - normally isolated - made hundreds of miles over the sea. To guide them back they had the usual navigation systems and also a radio frequency. However the Americans didn’t knew that Seville was using a very similar frequency, and that they had picked it up instead of their own. The compass indicated they were following a wrong route, but on board it was thought to be a malfunction. Finally they saw land, but didn’t recognize it.

“The flight was complicated from the start. We got up shortly after nine in the morning and had a lot of bad weather and turbulence. Visibility was reduced and we were forced to fly low most of the day. When we thought we were reaching the base, we came across a strange shoreline. It was possible to see the lights of a city or a village, but we could not identify it. With the low fuel levels, we had to try something to save ourselves”, Lyle Van Hook - the crew chief of the plane - explained me in 1998.

Crew training at Quonset Point, USA. October 1943. Standing: Samuel E. Thompson and Lieutenant Trum. Bottom: William R. Stultz, Paul Brugemann, Earl E. Sowers, R. E. Allen and Lyle Van Hook. Trum, Van Hook, Stultz and Sowers were on the plane that crashed in front of Faro. Sowers went missing,

(Picture: Lyle Van Hook)

“Any solution was complicated. The most obvious one was parachuting, but there were risks. Just beyond the coast the terrain seemed mountainous and we didn't want to take the plane in that direction because we could kill someone. If we jumped with the plane heading for the sea, some of us could end up in the water and drown. We still put in the parachutes on,” Lyle recounted.

With the fuel tanks almost empty, the commander, Richard Trum, changed the plans: “He had seen what looked like a beach and told us he was going to try to land. We dropped the depth charges and took our seats for an emergency landing.”

But what looked like a beach was in fact open sea, and when the landing gear hit the waves, the plane flipped and broke apart, dragging several crew members to the bottom. “When I realized I was in the water next to the rest of the fuselage. The back part was gone and the nose was sunken. I went on a wing with Rex McCoy, but when it started to sink we had to swim again.”

“We heard Lieutenant Trum shouting that he was clinging to a wheel and asking the crew to come to him. As McCoy was in no condition to swim, the captain pushed the wheel towards us. It was then that he warned us about one approaching boat”.

The impact of the plane, a few dozen meters from the boat, left Jaime Nunes and his companions terrified. “We were scared. Manuel, who was just a boy, cried and said we should run because they were going to kill us all, but the father and I decided to go and see what we could do. We heard the screams and started paddling towards them”.

Picking up survivors was slow. “We first found two of them swimming towards us. Then we collected what appeared to be the commander. He had buckled shoes and began to signal us to go get the others”.

Due to his injuries, Rex McCoy was the most difficult to put in the boat: “They had thick soaked clothes that made them very heavy. It was difficult to get all on the boat, but McCoy (the only name he remembered) – was the most arduous one. I grabbed him on one side and my compadre on the other. He was really strong. As we were pulling he grabbed my pants and ripped them apart. If he had got my meat, he would have take it all”, he said - laughing - as he pointed to his groin area.

William Stultz was even in worse shape. It was the last to be found and the one in need of most care. “He was on top of something being being dragged by the current. He never complained, not once. Never said a word. He was all white. One of the legs had lost all the flesh below the knee. He must have been in strong pain, but didn't show it”, emphasizes the fisherman.

“The captain (the way Jaime Nunes treats Lieutenant Trum) was talking, but we didn't understand anything. Then I realized he wanted to know if he was in Portugal or Spain. I told him, pointing to land, that it was Portugal. I repeated it two or three times and he became very happy, and hugged us”, explains Jaime Nunes.

Six were saved but five others followed the plane to the bottom of the sea.

Treated like thieves

In the city of Faro, the movements of the plane had been followed.

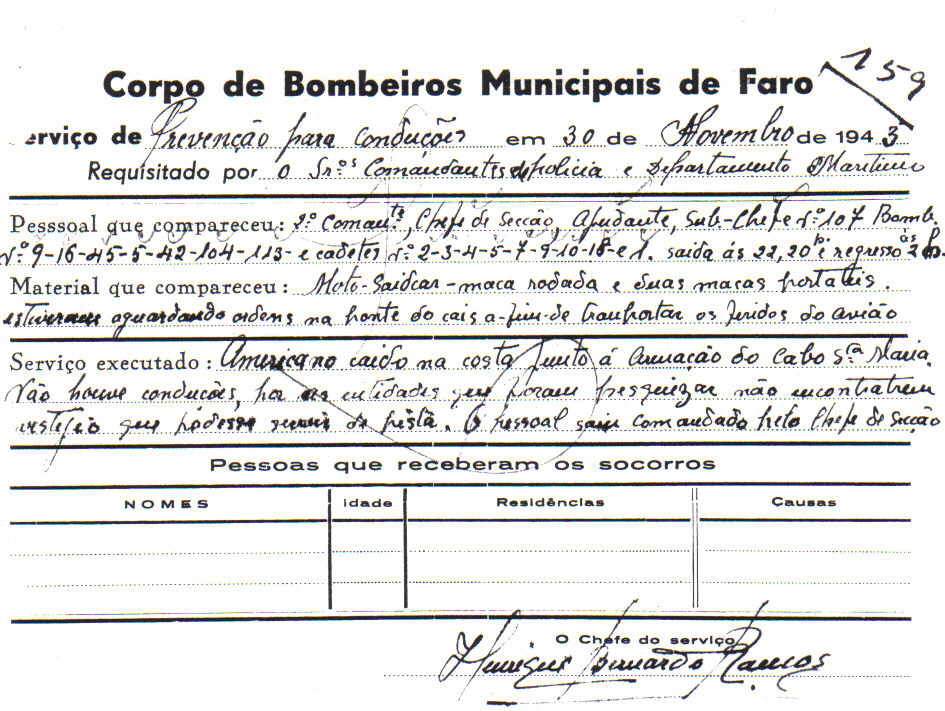

At around 10:20 pm, a group of firefighters was sent to the pier waiting for a small navy patrol boat that had been to search. Jaime Nunes recalls, “the engine of the navy gunboat, far away” but, at two in the morning, the firefighters demobilized as no signs of the aviators had been found.

Jaime Nunes was by then near a small entrance to the Ria Formosa in front of Faro – known as the Barrinha – waiting for a favorable tide to reach land. The boat was only five meters long and on board were nine people. They could barely move. During the wait, the sail served as a blanket for the castaways who were also wearing all the dry clothes on board.

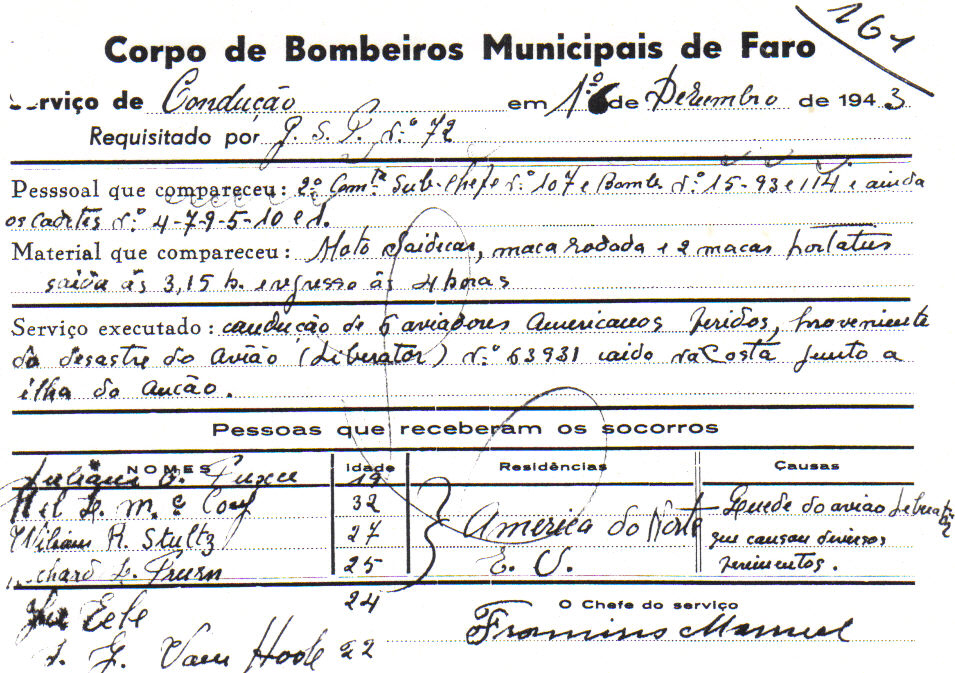

Faro fire brigade files related with aircraft crash.

(Municipal Archives of Faro )

The Americans got all the clothes, blankets, and provisions. Tobacco and coffee just disappeared. The smallness of the vessel required extra care when someone moved. “The most injured and McCoy were stretched out by the mast. The rest of them were distributed around the boat. The captain was at my side. We barely had room to row when we entered the Ria and headed for the pier”, explained Jaime Nunes.

They arrived at three in the morning and called the firemen again to transport the wounded to the hospital. “They were young men and only managed to take the most injured two. The others were clinging to us into the hospital. There where were neither lights nor doctors. The generator was turned on on purpose to assist the Americans. The doctors were called from home”, he recalled. The power outage was out as the city's generator was turned off at night due to rationing.

“The boat docked against a wall with stairs and I was grabbed by two people who carried me on by the shoulders into the hospital. They went fast and every half a dozen steps, I stamped my feet on the ground. I had lost the shoes and was barefoot. That hurts a lot”, recalled, in turn, Lyle van Hook.

At the hospital they were assisted by three doctors. “The captain was better, but the others were full of blood and glass”, explains Jaime Nunes, who left the hospital pushed by the medical staff, not knowing the true condition of the men he had saved: “The captain wanted us to stay, but the doctors said that we had to leave.”

Due to the severity of their injuries Stultz and McCoy were transferred to Lisbon the next day.

Lyle Van Hook, Richard Trum, Julian Pierce and John Eden were left recovering from minor injuries. “On the first day we had dozens of visitors. Most were nice people, but others asked questions about names, addresses, the squadron and the plane. The naval officer of the American Legation in Lisbon put an end to it. There were concerns with security issues that could not be forgotten”, stressed the American airman.

For Jaime Nunes, a small ordeal began. First, he was forbidden to visit the Americans, and then he was convinced by the American naval attaché to change the location of the accident beyond Portuguese territorial waters. In this way, airmen were considered sailors in distress and would be repatriated as soon as they recovered, rather than being interned. Obviously the new story brought tem problems with the Portuguese authorities.

The ruder treatment by the authorities, even caused a small popular uprising in the city.

In the hospital the Americans were given civilian clothes, food, wine and never forgot how they were taken care of. “Sister Noraldina, a Brazilian Catholic nun was responsible for us. She was like an angel sent from heaven. She taught us Portuguese words and also knew what each of us liked. She was always with us and I don't know when she rested because, even when we woke up in the middle of the night, she was there,” recalled Lyle Van Hook.

Only after a few days was it possible for the fishermen to visit the injured. “They gave us a picture of them inside the boat and we tried to make them comfortable. We didn't say much, but I think we managed to convey that we were very pleased to have them there”, said Van Hook. Jaime Nunes recalled the moment with joy: “The photograph had been taken for a newspaper, but due to the censorship it never was published. When we arrived the captain hugged me crying. They were very happy to be there. The wife of the English consul in Vila Real de Santo António was also very happy. She gave me more kisses than my mother”.

The visit was short-lived. “There was a table with a lot of food many important people. People with a lot of stripes on the shoulders. We didn't feel comfortable and ended up leaving. The captain gave us a few packs of tobacco and a bottle of port wine. It was our reward for saving them.”

On December 6, 1944, the four Americans were transferred to Lisbon and from there to their base in North Africa.

Left behind him was Jaime Nunes, thinking about a coat he had never seen again, after wrapping one of the aviators in it, and waiting for a reward that would arrive... fifty years later.

Delayed justice

In 1992 I became aware of this story when while looking in the Faro firefighters' archives for confirmation of stories about planes that had landed or crashed in the region. Ti' Jaime was introduced to me as the protagonist of one of the cases.

Taking advantage of the recent arrival of the internet, I set out to search for the six American aviators. After many contacts, letters and a lots of web-navigation, in the early hours of December 15, 1998, I received an email from Lyle Van Hook who, on the other side of the world, claimed to be well and in good health.

Angry because the American Naval Attaché had wrongly assured him that the fishermen would be rewarded, Van Hook sent a letter to the American ambassador. He told his story and emphasized that it was necessary to the United States to “correct a mistake committed upon the men” who saved him and the others.

Lyle Van Hook in 2001

Jaime Nunes with Lieutenant colonel Kelly from the US Army

(Picture: Luis Forra )

On the 8th of June 1999, the American Embassy promoted a small ceremony at the ALGARVE University and it was possible for Jaime Nunes - accompanied by family and friends - to see one of the men he saved. Trough a videoconference, two continents were connected and it was remembered what had happened in Portuguese and English.

In the end, Jaime received a plaque remembering the event and Van Hook, in tears, read a message highlighting the fisherman's feat: “I don't have the ability to speak your language and I'm not even sure how to pronounce your name. But for me, and for the others whose lives you saved that night, your name is synonymous to hero.”

More surprises…

In September 2001 I received a letter from Aram Y. Parunak, then a 91 years old who was the executive commander of the VB-112 squadron, in 1943. A friend had given him a message I had posted on the Internet in the early stages of my investigations. Therefore, he was unaware of the evolution of the case.

He had followed the case of William Stultz who had been transferred to an English hospital in Gibraltar. He had gotten worse and developed an infection. The Americans wanted him handed over, but the British doctors refused. The stalemate lasted about a month.

Parunak personally went to Gibraltar to try to transfer him, with no results. “No one took responsibility for releasing him,” he wrote. “By the end of the afternoon we concluded that there was no one we could talk to. We went back to where Stultz was and asked to speak to the officer in. charge. A NCO appeared saying he was the most senior. I replied that I was the most senior, and ordered him to release Stultz. I signed the order and returned to North Africa”. Stultz headed to the US where his foot and part of his leg were amputated.

I sent him an account of the evolution of the case and also an newspaper article that I had published with the story. All the episode until the tribute was there and also a reference to the fact that Jaime Nunes had lost his coat that night. Parunak thanked me and alo made a request: “A few months after the accident I took command of the squadron. I can't do much for Jaime Nunes, but I feel responsible for the actions of my men. So I should offer Jaime Nunes a new coat as a way of compensating him”.

At Christmas 2001, in a shop in Faro, I gave him a new coat in the name of Parunak. A message he sent was also read: “This Christmas season, we remember how the Son of God came into the world to save us from our sins and giving his life in our place. your valiant act follows that example, as your risked your own life for the salvation of others”.

Submerged bomber propeller.

(Arquivo Municipal de Faro)

Memorial in Faro - still under construction - remembering the moment when the fishermen rescued the crew from the bomber.

Months later I received a call from José Vieira, from Hisdroespaço, a diving school in Faro. He had found the wreckage of a plane off the city, in about 20 meters of depth. He had heard the story of the plane trough some fishermen and he had been looking for it for years. He was surprised when in an email exchange with someone the United States he got my contact. Even though we lived in the same city, we didn't knew each other.

In the following years, the “Faro bomber” or the “Faro B-24” - depending on the versions - became a popular place for divers from all over the country and beyond.

In 2008 I launched “Aterrem em Portugal!”, the book that told this and other stories about planes and aviators from belligerent countries that during World War II had landed or crashed in Portugal.

The following year I was contacted by Michael Pease, a retired British man who lives in Lagoa, Algarve. He had read the account of the rescue and thought that the fishermen deserved to be honored in some way. He looked for support, made contacts, gathered money and on September 7, 2022 his project came to fruition with the help of the Faro mayor.

The act of Jaime Nunes, José and Manuel Mascarenhas who on the night of November 30, 1943 saved Lyle Van Hook, Richard Trum, Rex McCoy, William Stultz, Julian Pierce and John Eden will be publicly remembered in a steel memorial…

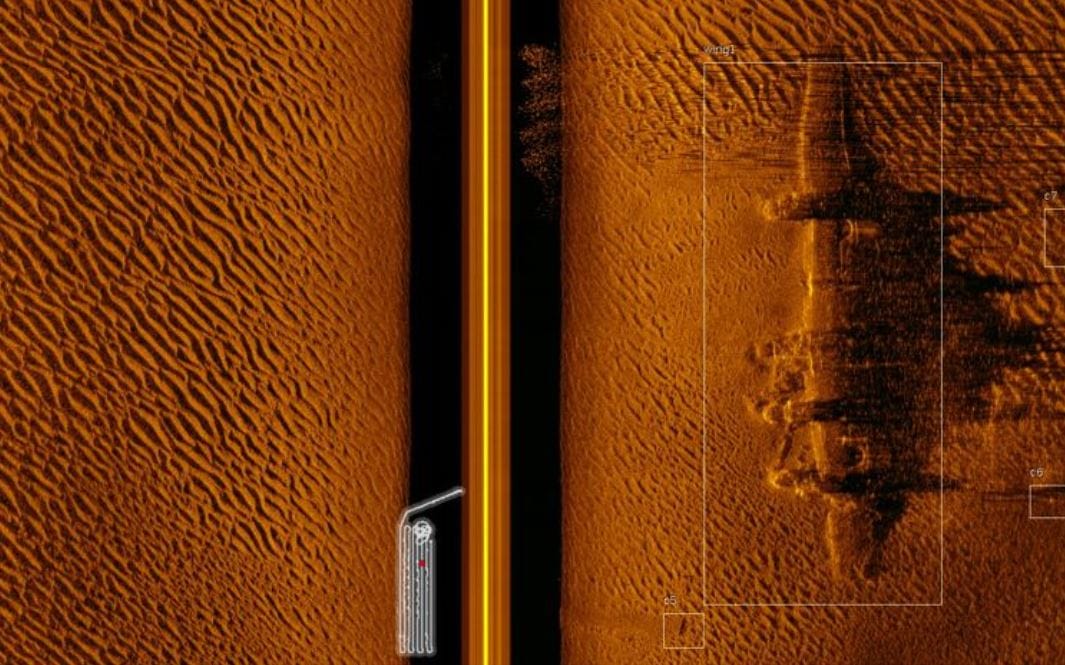

Image of the bomber captured by the side scan sonar used by the international team

Some members of the international team

In October 2022, an international team made up of archaeologists and other specialists under the tutelage of the American armed forces was in the Algarve to carry out a survey in the area. The collected data will now be analyzed in an operation that could take several months.

Carlos Guerreiro

Fontes/ Sources:

- Arquivos: National Archives UK, Kew (GB); Arquivo Histórico da Marinha (PT); Arquivo Histórico do MNE (PT);

- Sites: uboat.net;

- Livros: Shipping Company Losses of the second World War, Ian M. Malcolm; Lista dos Navios da Marinha Portuguesa, datas 1939 a 1945;