Ship – Ballot (Panamá) & Induna (GB)

Birth place – Ericeira

Birth date –

Death date –

Father – Custódio da Luz

Mother – Maria da Nazaré Lopes da Luz

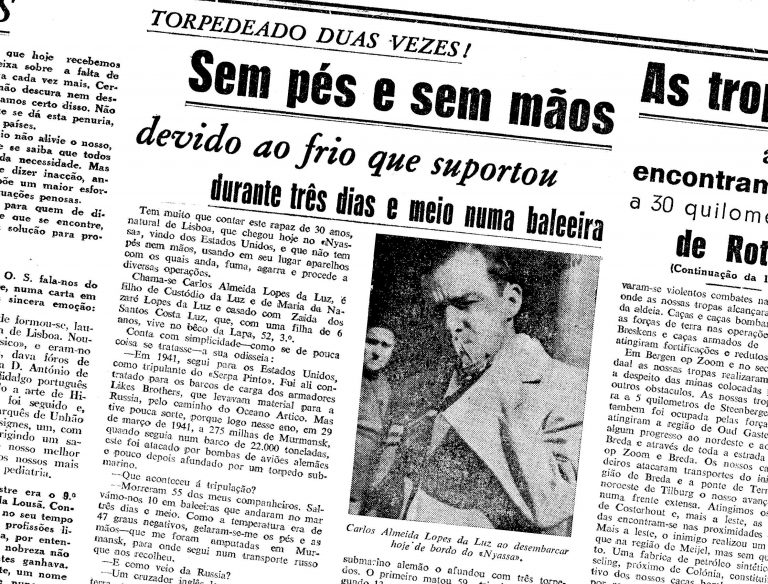

New cut about Carlos Luz published in the newspaper "Diário de Lisboa" on the Day he arrived in Lisbon

On October 31, 1944, Portuguese seaman Carlos de Almeida Lopes da Luz, aged 30, disembarked in Lisbon from the Portuguese Ship Niassa, and could not pass unnoticed not only because he had journalists waiting for him, but also because he had no feet or hands, “using instead devices with which he walks, smokes, grabs and performs various operations”, as the newspaper Diário de Lisboa described it at the time.

Carlos Luz was returning home in Beco da Lapa, number 52, Lisboa, where his wife Zaida dos Santos da Costa Luz and his six-year-old daughter were waiting, after a three-year absence that had taken him from Portugal to the USA, and from there to the frozen seas of Russia, where he lost his hands and feets to the cold.

When, on November 17, 1941, he left Lisbon for New York, as a crew member on the ship Serpa Pinto, he had already decided to desert to seek better living conditions. In Portugal, the salaries of seafarers were low, the future was not promising and therefore the desertion of Portuguese seamen as soon as they arrived in the USA was a normal event. The situation was sometimes so serious that some ships were forced to postpone departures due to lack of personnel…

As soon as he left the Portuguese ship, he went to the offices of the Lykes Brothers Steamship Company, determined to improve his life and that one of his family. In November 1941 the US was still neutral, but a few weeks later the Japanese attacked Peal Harbor and suddenly Carlos Luz found himself embroiled in a world war.

On March 16 of the following year, in Reykjavik, Iceland, Luz – now a crew member of the Panamanian-flagged ship Ballot – joined the PQ-13 convoy bound for Murmansk, Russia. The Arctic convoys - which supplied war material, especially American, to the Russians - became known for their harshness, inclement conditions and exposure to German attacks.

On 24 march the PQ-13 was hit by a violent storm that dispersed the 19 merchant ships and the four escorts, splitting them into two groups, with other four units sailing independently. On the 28th they were spotted by German planes that carried out a first attack sinking two vessels. The Ballot was also hit and Carlos Luz, with 15 other crew members, including one more Portuguese, left the ship. The commander would later say that he never gave an abandonment order and the men just demanded to leave.

In fact, the Ballot was repaired by the rest of the crew and managed to continue its journey to the Russian port, where it arrived two days later.

The rescue boat was picked up by one of the escorts - the HMS Silja - and the men re-embarked on the British Induna, but both became trapped in the ice while the rest of the fleet continued to Murmansk. Freeing the boats took several hours and the next day they were caught by another storm that separated them again.

On the 30th Induna was torpedoed by U-367, caught fire and sank. Forty one men managed to escape in two lifeboats. Carlos Luz was with them and, a newspaper article, mentions also the presence of another Portuguese named José Arruda, from Espinho, who died from exposure.

The website u-boat.net, does not mentions José Arruda, but gives assurances that among the fatal victims is another Portuguese, named Avelino da Silva Larangeira (possibly Laranjeira), with 45 years.

Only on 2 April a Russian minesweeper found the lifeboats when eleven of its occupants had already died. Two more would die in a Russian hospital. Almost all the others showed signs of exposure to the icy winds that reached minus 20 degrees. Many lost feet or hands.

In the following months Carlos Luz feet and hands were amputated after several surgical interventions. He returned to New York where he started using orthopedic devices that allowed him to walk and grasp.

During his time in the US he waited for a decision on a compensation, one issue still not resolved when he arrived in Portugal in October 1944.

His story was known in Portugal since late 1943 when the newspapers told about his misadventures. When Niassa left him at the pier, he was intercepted by elements of the Portuguese political Police PVDE who reminded him of the Serpa Pinto's defection. They would let him go home - perhaps due to the presence of journalists or, according to the newspapers, "given his physical circumstances" -, with the obligation to report to the police headquarters the following day.

I was unable to find out what happened to him in Portugal or if the compensation was ever paid.

Carlos Guerreiro

Sources

Induna - uboat.net § Diário de Lisboa § Diário de Notícias § O Século